Published in Columbia News Service on 5th November, 2025

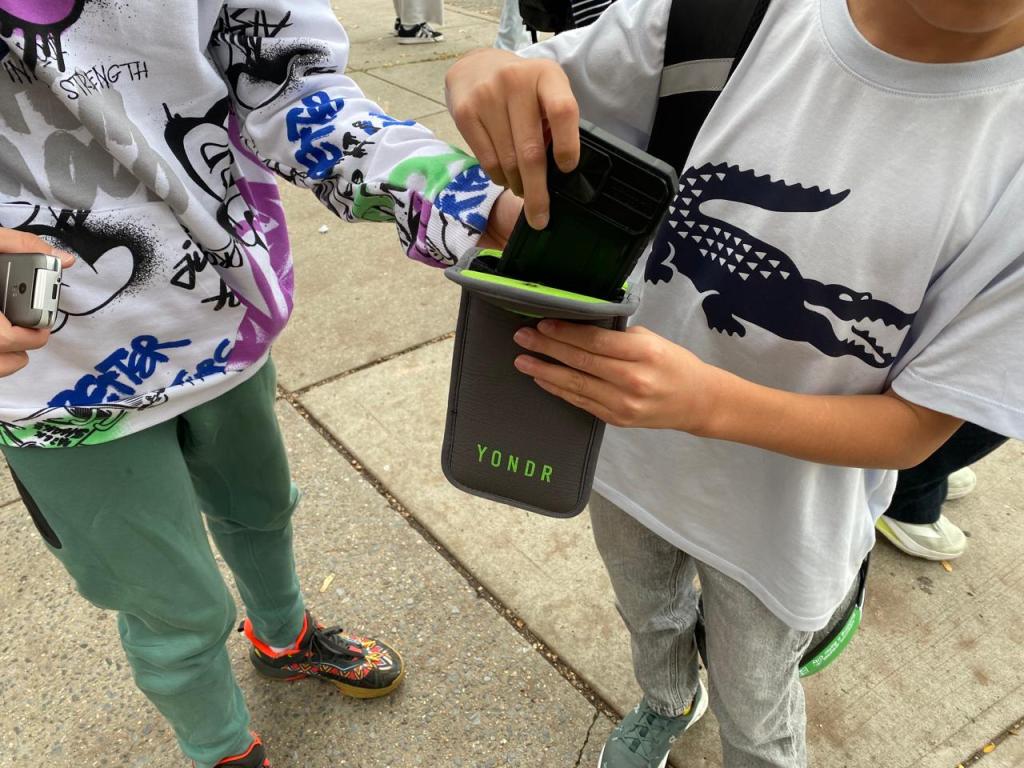

A student removes his smartphone from a Yondr pouch. (Credit: Karthik Vinod)

At about 2:30 p.m. on a recent fall afternoon, students streamed out of JHS 190 Russell Sage in Forest Hills, Queens. The younger ones were quick to yank their smartphones from a Yondr pouch, with its magnetic pin that keeps devices secure. Their parents, waiting by the curb, hardly seemed to notice: all were transfixed by their own devices.

In May, New York Gov. Kathy Hochul banned smartphone use in classrooms as a way to limit the distractions that can affect student learning and to improve mental health. More than a month into the ban, students offer mixed reviews.

Some students say implementation is uneven. Certain teachers take a hardline view and whisk away smartphones in any setting, even outside the classroom.

“I feel like you should use your phone when it’s not class,” said Zuhro Ahrorkulova, a student in sixth grade at Russell Sage.

Other teachers take a more liberal approach, letting students use their phones during lunch breaks.

But the biggest criticisms from some—all of whom welcomed the restrictions—is that it does not seem likely to achieve its goals. The restrictions neither truly address addiction, they say. Nor do they address the need for parents and teachers to engage more fully with students inside and outside of school, something that has been shown to have a positive effect on student well-being.

Students who are anxious and withdrawn just find other forms of distraction in class, like daydreaming. “If you’re not going to be distracted by a smartphone, you might as well be distracted by something else now. You’re not really solving the issue,” said Alexander Tyler Lau, a 16-year-old sophomore at Russell Sage.

Noa Almog, who started middle school this year, said she believes the restrictions will not curb cyberbullying either, since schools are concerned with curbing screen time only during school hours, and plenty of online bullying happens after school.

The students’ skepticism is echoed by some experts. Christopher Ferguson, a professor of psychology at Florida’s Stetson University, says that research on the topic has yielded mixed conclusions about whether phone bans improve grades, attention, and mental health, or whether they reduce bullying. A large study from the United Kingdom found that the bands don’t mean “better mental well-being” for teens. Another study from Norway found improvements, like decreases in bullying and higher GPAs. Closer to home where Ferguson lives, in Orlando’s Orange County School District, a similar ban was enforced two years ago. “It actually went way better than we thought it would,” a media report quotes a parent saying, about the smartphone bans, back then. Students would apparently play board games and socialize more. Except, media reports remain the only anecdotal evidence.

“It’s not that I want smartphones in the classroom necessarily,” Ferguson said. “It’s more that people are making grandiose promises that are not rooted in science.”

Public data that Ferguson accessed from the school district showed that mental health referrals rose in the aftermath of the ban. In late October, the private, non-profit National Bureau of Economic Research published a study online scrutinizing aggregated student records from a Florida school district, in the aftermath of the ban – and the first reported in the United States. The paper, which hasn’t yet gone through a peer review process, found that suspensions shot up about 50 percent the first year in the school district, before dropping and then plateauing. Black students were disproportionately representative of this cohort. Student test scores, meanwhile, reported a marginal improvement by a percentile in the second year of the ban.

The study’s main takeaway, according to its co-author, Umut Ozek, a senior economist with the RAND Corporation, was the presence of a “transition period” when schools are getting accustomed to implementing the ban. He said during the first month, schools were more relaxed with the ban, avoiding any means to snatch phones away. But things got worse, before they got better. And Ozek has a theory why this might be the case.

“Once we get to a point where students know that cell phones are not going to be permitted on school property, we do see improvements in outcomes,” Ozek said. He conceded that it would take a lot more than just one study to upend the established consensus on mixed conclusions available, to extrapolate the case of the Florida school district with more school districts, and in other states. For one, the implementation varies between states. And, there just aren’t enough studies yet. “We need more research on this for sure,” Ozek said.

Ferguson said students today are as likely to find lessons as boring as students did generations earlier—but that the smartphones make it more obvious to teachers that they are not doing well engaging their students. “We’re not doing anything about the poor quality of instruction in schools, how boring and repetitive it is,” he said.

Improving student outcomes is a social endeavor, requiring participation from both teachers and parents. Two studies, published in 2021 and 2023 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, suggest kids tend to have a lower risk of suicide, depression, violence, and high-risk sexual behavior when they feel better connected to their family, peers, and community. Removing phones doesn’t necessarily create the community kids need either, Ferguson said. They do not help those students growing up with an inadequate support system, those with weak familial bonds or emotionally unavailable parents, or those who live in poverty, Ferguson said. “Those are the things that really have an impact on kids.”

Almog, who is 11, says screens can fill a void for some people. “The first time you see snow, you want to see it again. Not because you’re addicted, but you just want to see it again,” she said. “It’s the same with technology.”

Vera Feuer, a child and adolescent psychiatrist and medical director at Northwell Health, agreed that smartphone bans are not a full solution to producing well-rounded children. But “it’s an important step towards allowing our kids in schools to be able to learn in different ways, which I do think ultimately is better for them,” she said.

It benefits students who often miss out on peer-to-peer interactions at school. “School is such an important place to learn those skills in a safe environment … feeling belonging to a school community.” Feuer said. “That sense of belonging and community is just so powerful, and the skills that you need to be able to be in that serve you so well in life right later on.”

Almog agrees with the new policy: “Phones should be banned in classrooms.” But parental engagement is what kids need most, Almog said. “It’s not the teacher, not the kids, or anyone around you. It’s literally the parents.”

Leave a comment